In a major update on how India’s national song is to be recognised and performed, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has issued formal guidelines that bring the original version of Vande Mataram back into official use.

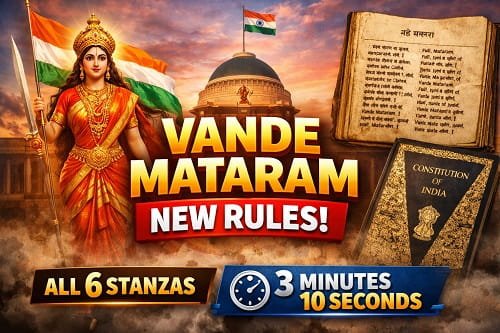

On 6 February 2026, the government released a detailed order specifying that all six stanzas of Vande Mataram — including the four verses that were previously left out in public performances — must now be sung or played at a range of official and ceremonial occasions across the country.

This directive arrives at the close of India’s year-long 150th anniversary celebration of the composition of Vande Mataram — a milestone that prompted nationwide reflection on the song’s history and meaning.

What the New Order Says

According to the Home Ministry’s notification:

● The official version of Vande Mataram for public occasions will consist of six stanzas, running for 3 minutes and 10 seconds when sung or played.

● This official version must be rendered at key national and state functions. These include:

○ Flag-hoisting ceremonies and parades.

○ Civilian award ceremonies such as the Padma Awards.

○ Arrival and departure of the President of India and governors at official events.

● When both Vande Mataram and the national anthem, Jana Gana Mana, are performed at the same event, Vande Mataram will be played first.

The directive also says that the audience must stand at attention whenever the national song is being played or sung, similar to standing for the anthem. The only exception is in cinema halls or during films and newsreels where standing might disrupt viewing.

Morning assemblies in schools are now advised to incorporate Vande Mataram into their programmes, and the Ministry expects widespread participation and respect for the song’s performance.

Why This Is a Big Change

Since India’s independence, it was common practice to perform just the first two stanzas of Vande Mataram at public gatherings. These stanzas are more neutral in imagery and widely accepted across diverse communities.

The later four stanzas include references to Hindu goddess imagery, and during the freedom struggle and early years of independence, leaders chose to omit those verses from official recitation to avoid religious objections.

In 1937, under the leadership of prominent Congress figures including Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Rabindranath Tagore, a resolution was passed to use only the first two stanzas for public occasions. This decision shaped how the song was practised for decades.

Official vs. National Anthem

It’s important to understand that Vande Mataram is India’s National Song, not its National Anthem. The anthem, Jana Gana Mana, was composed by Rabindranath Tagore and was adopted officially as the national anthem in 1950. Vande Mataram was also given a special place of honour because of its role in the freedom movement, but it is distinct from the anthem.

The 2026 directive now brings Vande Mataram closer to the level of ceremonial protocol already observed for the anthem, with set duration, sequence and expectations for public conduct.

Public Reaction and Political Debate

News organisations and commentators note that this guideline is likely to spark debate. Some political leaders have welcomed the move as a way of restoring the song’s original form as written by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, while others see it as a politically charged step that could reignite cultural debates around national symbols.

In Parliament during late 2025, lawmakers from various parties had already engaged in heated discussions about the song, its meaning and how it should be observed in modern India.

What Happens Next?

With detailed instructions now issued, it falls to state authorities, educational institutions and government bodies to implement the guidelines. Schools are expected to begin incorporating Vande Mataram into daily assemblies, and public functions will now include the full six-stanza performance protocol.

The government’s move marks a turning point in how one of India’s most historic patriotic songs will be treated in public life — embedding it more deeply into the ceremonial fabric of the Republic.